Liquefied natural gas (LNG) is natural gas, predominantly methane, converted into liquid form for ease of storage or transport. The liquefaction process involves cooling the gas to around -162 °C and removing certain impurities, such as dust and carbon dioxide.

As a liquid, LNG takes up around 600 times less volume than gas at standard atmospheric pressure, which facilitates its transportation over long distances without the need of pipelines.

When it reaches its final destination, LNG is usually re-gasified and distributed through pipelines. LNG is also increasingly used as an alternative fuel for ships and lorries.

Importance of LNG for the EU's security of supply

The EU's gas demand is around 330 bcm per year. Natural gas currently represents around a quarter of the EU's overall energy consumption. About 26% of that gas is used in the power generation sector (including in combined heat and power plants), and around 23% in industry. Most of the rest is used in the residential and services sectors, mainly for heating buildings.

Ensuring that all EU countries have access to LNG markets is a key objective of the EU's energy union strategy as it can contribute to diversifying gas supplies, thus improving EU energy security in the short-term, while more sustainable solutions towards full decarbonisation by 2050 are established.

Key facts

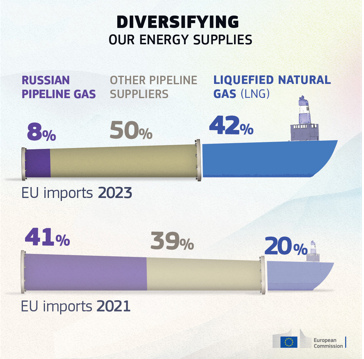

Increasing LNG imports from trustworthy global partners is key to fully eliminating the EU’s reliance on Russian fossil fuels. The 137 bcm of pipeline gas imported to the EU from Russia in 2021 was reduced by 82% to 25 bcm in 2023. (Source: European Commission calculation based on LSEG (Refinitiv) and ENTSO-G data).

The EU’s 14th package of sanctions against Russia includes measures which target LNG specifically. The package prohibits all future investments in, and the provision of services and goods to, LNG projects under construction in Russia. It will also prohibit, after a transition period of 9 months, the use of EU ports for the transshipment of Russian LNG. Moreover, the package prohibits the import of Russian LNG into specific terminals which are not connected to the EU gas pipeline network.

Each step to phase out Russian fossil fuels brings the EU closer to a more secure and sustainable energy supply, in line with the objectives of the European Green Deal and the EU's 2030 energy and climate targets.

Key partners

Following the Russian invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 and its weaponisation of Europe’s energy supply, the share of Russian pipeline gas in total EU energy imports has fallen dramatically from 41% in 2021 to about 8% in 2023. This has been replaced mainly by LNG from the US, which supplied 46% of EU LNG imports in 2023 and reliable pipeline gas imports from Norway (49% compared to 30% in 2021), North-Africa (19%) and Azerbaijan (7%).

Global LNG supply is expected to continue to rise slightly in 2024, driven by increases in production and liquefaction capacities in LNG exporters. This will ease the pressure on global gas markets and lead, together with historically high level of gas stocks and subdued demand, to lower prices on the European markets.

The US is playing an increasingly important role in the EU’s gas supply. At the end of March 2022, the EU and the US adopted a common declaration on increasing LNG trade, and expressed interest in further increasing EU LNG imports from the US by 15 bcm in 2022 compared to the previous year. This goal was reached at the end of August 2022, 4 months in advance of planning.

The largest LNG global exporters in 2023 were the United States, Australia and Qatar. Global liquefaction is set to further increase as new plants in the United States and Australia will come on stream over the next few years.

(Sources: Pipeline data - ENTSO-G; LNG data - European Commission calculation based on LSEG (Refinitiv) and ENTSO-G.)

Infrastructure and financing

The EU has steadily increased its LNG import capacities by developing new LNG regasification and port terminals and building a liquid gas market which provides robust resiliency to possible supply interruptions from the remaining Russian pipeline imports.

However, bottlenecks and infrastructural limitations still exist in some regions. Several EU countries are increasing their LNG import capacity by accelerating investments in LNG terminals. The EU’s LNG import capacity grew by 40 bcm in 2023 and an additional 30 bcm is expected to become operational in 2024.

Based on the EU’s list of Projects of Common Interest (PCIs), the LNG strategy includes a list of key infrastructure projects which are essential to ensure that all EU countries can benefit from LNG.

With any new infrastructure, commercial viability is very important. For an LNG terminal, its utilisation across a whole region, or the choice of lower costs and more flexible technologies - such as floating storage and regasification units (FSRUs), may considerably improve its viability. Regasification terminals in EU countries have an annual nameplate capacity determined for environmental reasons. Divided throughout the year, the weekly nameplate capacity can be exceeded in periods of more intensive LNG inflows.

LNG terminals, like other energy infrastructure, are financed through end-user tariffs (paid for by all gas consumers as part of their monthly gas bill). In some cases, gas companies finance construction in exchange for the right to use the terminal through long-term capacity booking. But even with a sound business case, financing may still be a challenge in some cases.

For projects that are particularly important for security of supply, EU funds, such as the Connecting Europe Facility, could potentially help fill the financing gap.

EIB loans and the European Fund for Strategic Investments may be other sources of long-term financing.

Documents

Factsheet: EU-U.S. LNG TRADE U.S. liquefied natural gas (LNG) has the potential to help match EU gas needs (February 2022)