In a detailed interview, Catharina Sikow-Magny, Director for the Green Transition and Energy System Integration in the European Commission’s Directorate-General for Energy, reflects on the situation for renewables in the context of the energy crisis and explains how previous energy infrastructure investments have helped the EU respond to the energy crisis last year. She also shares her thoughts on the recent Electricity Market Design proposal and ongoing moves to push for more action to reduce methane emissions.

Following the Russian invasion of Ukraine, the EU scrambled to find alternative sources of gas. Is that going to slow down the energy transition?

The short answer is no. The current crisis after Russia attacked Ukraine led, indeed, to a shortage of gas and to very high prices in the gas market, and also then in the electricity market. This triggered our investments in alternative sources, not only alternative gas sources like liquefied natural gas (LNG), but also alternatives meaning renewables. If we look at the figures from last year: there were 57 Gigawatts (GW) of newly installed renewable power in the EU. Out of this, 41 GW for solar, which is 47% more than investments in 2021 - and 15 GW for wind, which is 34% higher than in 2021. What is the forecast for 2023? The industry says that investments would amount to some 53 GW of new solar capacity and 16 GW of new wind capacity. So overall, almost 70 GW of new renewable capacity this year.

So, all in all, the crisis has actually accelerated investments in renewables. And this will be the permanent way out of our dependency on Russian gas.

We have now got a political agreement on the Renewable Energy Directive. It still has to be formally adopted (which we expect to happen in June), but can you already say what you think the main benefits for the EU of this revised text are? Critics will obviously say, “you have not achieved the 45% target” - what can you say in response to that?

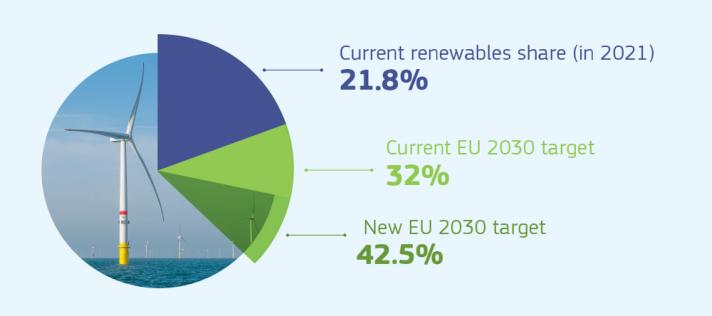

Indeed, the co-legislators agreed on the renewables directive very recently – and we hope that the final legal texts in all EU languages can be formally adopted in the near future. The important objective agreed upon is that, in line with the REPowerEU and FitFor55 proposals, the overall renewables target has increased to 42.5% by 2030. Compared with the 2030 target of 32% set in 2018, this is a significant change upwards. We also have an aspiration to reach 45%, even if not legally binding. This means that we need to double the share of renewables in our mix – from approximately 22% in 2021 to this new figure by the end of the decade.

Source: renewable energy targets

This overarching target is combined with enhanced ambition across sectors – in particular where progress has been slower. We see that the power sector has already been decarbonised to a large extent. This is the low-hanging fruit if you wish, and now the focus needs to move to buildings, industry and transport - which are more complex to decarbonise, technically and cost-wise. So, in the new renewables directive, we will now have binding sub-targets for these sectors, as well as for renewable hydrogen, both for industry and transport. This will create the pull effect to get these sectors not only more decarbonised but also decarbonised faster.

And to complement these targets, the new rules also include very ambitious provisions on permitting – such as having binding timelines for the authorities - so that we can accelerate permitting, thereby speeding up installation and ensuring that we can then meet our ambitious targets through actual construction on the ground. So, put briefly, these are the key elements of the renewables directive amendment. Obviously, there are very many other aspects, but these are the headline elements.

Can we say that we have managed to achieve more in this new directive because of the war?

I think this is probably the case. Let’s not forget that the 42.5% target agreed now is higher than the original ‘Fit for 55’ proposal of 40% that was first tabled in July 2021.

I think this is probably also true for the speeding up of investments – notably on the agreement to have a real impact on unnecessary permitting delays. We made two proposals in the past year on permitting - one was a crisis-related temporary measure on accelerating the process; the other was to include the provisions of that temporary crisis regulation in the renewables directive to serve as a permanent solution for the future. So, I think those elements are certainly crisis-related - the realisation that our targets were not enough, and the need to ensure that projects can be built faster than in the past.

You mentioned hydrogen. How are we possibly going to achieve our hydrogen targets: imports of 10 million tons and domestic production of 10 million tons by 2030?

First of all, the renewables directive is a key element in this puzzle. We need to have the renewables in place to produce hydrogen. So, we need to work both on demand and supply. So, we need to work both on demand and supply. We can foster supply through the renewables targets and binding targets for industry and transport. They will be key. We also need to have a robust certification system in place, to ensure that any ‘renewable hydrogen’ that is being produced and consumed, really is renewable. On this point, the Commission has proposed secondary legislation that is still under scrutiny in the Council and the Parliament until around mid-June. But as soon as this approval process is complete and this delegated act is in place, then the certification of renewable hydrogen can take place –and the market can really get going.

Obviously, hydrogen is a new energy vector which is still more expensive when produced from renewables than fossil-produced hydrogen. So, we need also to create an environment where consumers – such as industry and heavy transport - can and will buy this fuel, even though at this stage it is still more expensive than non-renewable hydrogen. On the one hand, the targets will play a role, but there are other policy tools too (as identified under the 2020 hydrogen strategy). A proposal on market rules for hydrogen is under discussion (and should be agreed this year). Infrastructure issues are covered by the Trans-European Networks for Energy rules, which are already in place. Last, but certainly not least, the Commission is also working on the Hydrogen Bank, as a hub which will contribute to covering the price difference I mentioned between renewable hydrogen versus fossil hydrogen. This bank should be operational by early autumn and provide the support needed to boost the uptake of renewable hydrogen.

So, the EU domestic production part is almost ready and is clear. We are also working on the external parts - the imports part that you mentioned - in order to be able also to make sure that the EU can purchase the 10 million tonnes as intended.

But most of the investment that is needed will be private, it is not coming from the EU budget?

All investments - be it for renewables, be it for infrastructure - will primarily come from the private sector. EU funds alone are not sufficient and it is not their role. They act as a seed, as leverage. In certain cases, where really the market cannot deliver, the EU support comes as a last resort and is the critical element in getting a project over the line.

The regulatory framework for hydrogen that we are developing will cover investments and determine how the infrastructure will be paid for. In practice, this will typically mean user tariffs in most cases, as we have for the electricity grids, as we have for the fossil gas grids.

Another major contribution to moving away from Russian gas should come from biomethane. Will we manage what we are aiming for there and how?

Biomethane is already a well-established technology. In the REPowerEU plan, we have now established a target for 35 billion cubic meters (bcm) of biomethane production by 2030.

The advantage of biomethane is that it is available across the whole EU – mainly as an ‘agricultural side-product’, if I can call it that. With this, it can be directly fed into the gas grid with relatively little investment and consumed then instead of fossil gas. Denmark is one of the leading EU countries in taking up biomethane and they already today replace 35% of their fossil gas with biomethane. The main challenge is simply that it is widespread, so one needs to organise the collection of it so that it can be then fed into the gas grid.

The 35 bcm target by 2030 is a very feasible target. According to our calculations, it is something that can definitely be achieved through enhanced coordination, awareness raising and some investments (but much more small scale than in the other sectors we’ve discussed).

Turning then to electricity market design: we have had the proposals, they came out in March, and we have had a discussion with EU countries. How do you feel that dossier is looking? Is it realistic to get an agreement by this time next year?

Let me start by recalling that the proposal has three key objectives. These are

- to protect and empower consumers, even more than is the case today -learning from the crisis

- then, enhancing the competitiveness of our industry, in the context of global competition and the Net-Zero Industry Act

- and thirdly, boosting investments in renewables and low carbon technologies as well – as I mentioned earlier

So, it is a targeted proposal with impact. What we have seen in the first discussions is overall a very positive welcome – not only from the co-legislators but also from the industry and from regulators. The discussions that are currently taking place are focusing first of all on clarifying the text and then on a few elements, obviously where either EU countries have questions or different ideas, or where the European Parliament has different ideas.

The sort of questions that we are looking at are

- Are the incentives in the proposal sufficient to accelerate investments, or would we need something even stronger?

- How do we ensure that consumers are not locked into the current high prices?

- How do we get more transparency in the trading market and how can we ensure then that there is no risk of any kind of manipulation?

- And, how do we ensure that the design of the market is future-proof - also in case of future shocks that would probably be very different than the current crisis situation?

- At the same time, it is important to ensure that the EU single market will continue to deliver its many benefits to consumers, in particular by avoiding measures risking market fragmentation

All in all, I do believe that the co-legislators can, and there is a willingness to, conclude the negotiations this year – and, obviously, the earlier this year it happens, the better. We could then be even better prepared for the coming winter.

Turning then to infrastructure, and REPowerEU, talking about Projects of Common Interest (PCIs), what are their main challenges? Is there a danger that we lock ourselves into fossil fuels? Where do you see the PCIs going from now on?

Let me again start by recapping the objectives of the policy we are speaking about, which is the Trans European Networks for Energy (TEN-E). It has three broad objectives: secure supply, sustainability, and affordability. And, the Projects of Common Interest are the concrete projects that address these objectives in the best way – allowing us to address the EU’s most urgent cross-border infrastructure issues rapidly.

The process is run every two years so that we can flexibly adjust to needs, changes in the market etc. Gas investments have been part of the process since the beginning and we have invested in a number of gas projects which have turned out to be critical in the current crisis. So without them, there would have been parts of Europe that would really have been in the cold. The projects include, just mentioning a few examples

- the interconnector between Poland and Lithuania, running up also then to Finland

- interconnectors between Bulgaria and Greece

- reinforcing of the Bulgarian and Romanian grids

- LNG terminals in Poland and Croatia

These projects have shown that in a crisis, gas could flow to where it was needed. This has changed now, however, because in the revised TEN-E regulation fossil gas is not accepted as PCI-compatible anymore. So, the current work on preparing the 6th list of PCIs, due at the end of this year, will no longer include fossil gas projects (apart from two exceptions (for Malta and Cyprus) that were derogations agreed by the co-legislators.)

The reasons for this change are twofold: the gas grid is already rather well integrated in the EU; and secondly, the decarbonisation process which will see our gas demand reduce. At the same time, in the context of the preparation of REPowerEU, there was an assessment of whether we are really sure that we have identified all the projects in the EU through the PCI process that are necessary for the security of our energy supply - because the disruption of Russian gas was not a scenario that we were necessarily looking at. Very few additional needs were identified, so the TEN-E policy and the PCIs have addressed largely the needs we had.

The PCI selection process is ongoing, and between November and December, the Commission will adopt the 6th list. But the big challenge, the new challenge, will be the development of offshore grids. There have been a few high-level meetings recently, including the North Sea Summit in Ostend, where the importance of offshore wind has been acknowledged by heads of state and government and energy ministers. Our President and Commissioner were both present there, which indicates the political salience of future investment in this technology. Another priority will be the development of the hydrogen grid of the future. These two new elements will require a lot of work. The Commission needs to consider now how to assess the candidate projects; cost-benefit analyses, and what scenarios we are looking into, are occupying colleagues' time now.

Can you say something about a new concept which is the Projects of Mutual Interest?

Projects of Mutual Interest (PMIs) are indeed a new element in the new TEN-E regulation. The concept applies to projects connecting one EU country with a non-EU neighbour – we are mostly thinking about the Balkans, Ukraine, Moldova, North Africa and Norway. These projects, as they are part of the Trans-European Network framework, need to provide benefits for at least two EU member states in terms of secure supplies, sustainability and affordability. We are not speaking here about an external relations cooperation instrument.

And finally, how are we doing on methane emissions? And what is the situation internationally?

First, we need to keep in mind that methane is a much more potent greenhouse gas than carbon dioxide. Methane alone accounts for 25% of global warming.

What we are speaking of here is methane leakage - gas let into the air. On the one hand, this is contributing to global warming, but at the same time it is also lost revenues and, depending on where the leak is, it can also be a safety hazard.

There are three sectors with methane emissions – energy, agriculture and waste. In our proposal, we focus on energy, which is more or less the low-hanging fruit.

We have proposed rules for leak detection and repair so that we know where leaks are happening and that they are repaired in a certain, short time period. Most of these investments are cost-effective because the gas that is not leaking can be sold to the market. So they are investments that should be taking place even without our regulation in the gas sector.

The proposal is now in the co-legislative process. It's the first legal proposal the EU has made on methane and leakage, and it is the most ambitious in the world. The European Parliament has recently voted through its position, the Council is working on its General Approach, and we hope to see the conclusion of these inter-institutional negotiations by the end of the year.

The proposal only covers EU territory. We do not legislate for what happens outside the EU. Having said this, there is very strong cooperation between the EU and many world players to address the issues at the international level. I highlight here the US, but also Japan with whom we cooperate very closely. The US for instance also has an important framework in place.

We need to stop the practice of ‘flaring’ – where gas is leaking when you’re extracting oil and is then burned because you don't need it. If we can simply collect this gas, we could even see it traded (as an alternative to Russian gas). This is why international cooperation on methane emissions is essential. We have already made some progress, but need to do more.

Our intention is to enhance international cooperation to make sure that there is no leakage. For example, there is work on satellite detection, where the EU is very strong so that we can see from space where these leaks take place and then plug them. We work through the UN system, together with countries like the US, in order to raise awareness.

Related links

Details

- Publication date

- 16 May 2023

- Author

- Directorate-General for Energy